Bottling & Labeling

Before bottling, we make final adjustments to the SO2 and CO2 levels in the wine. Then, when the desired blend of wine is ready in the mixing tank,

we sparge each bottle and then fill it with wine

we insert a cork

we cap the top of the bottle with a foil

we put a printed label on each bottle

We sparge, fill, cork and cap a bottle in a continuous process. This takes about 50 seconds a bottle for a single person. For two people working together, It takes around 30 seconds per bottle, i.e., 100-120 bottles per hour. Labeling is done later. The picture on the left shows the sparger at the bottom connected to an argon bottle and the bottler filler on top of the sparger. The picture on the right shows a friend, Jost von Allmen, in action with the Sparger (bottom left), the Bottle Filler (left), the Corker (middle), and the Foil Spinner (top right). This page explains the final adjustments and the four bottling steps..

Final adjustments in SO2 and CO2

We make one, possibly two, final adjustments to the wine just before it is bottled. The first is adding SO2 to enhance its resilience against spoilage organisms; the second is increasing the level of dissolved CO2 to enhance the perception of fruitiness if desired.

We target a level of molecular SO2 at 0.50 ppm right before bottling. We discussed the reasoning for SO2 additions in the Winery section, Step #8: Adding SO2. Since we stopped adding SO2 during elevage, we can safely assume there is no free SO2 in the wine before this final adjustment. We calculate the amount of KMBS (Potassium Metabisulfite) that needs to be added to reach the target level for molecular SO2 of 0.5 ppm. The Laboratory Section explains the details on page "Measuring and Adjusting SO2.".

If we decide that the perceived fruitiness of the wine needs a boost, then we measure the dissolved CO2 in the wine with a Carbodoseur. For Bordeau-style red wines, 400-800 ppm is a reasonable target range. To increase dissolved CO2, we add dry ice, which is frozen CO2. The amount of dry ice added depends on the volume of wine to be treated and the assumed uptake of the CO2 gas as it bubbles through the wine. The "Measuring Dissolved CO2" page in the Laboratory section describes the Carbodoseur and the formula. We start by adding 30%-50% of the required dry ice and retest before adding more.

Filling the bottles

We buy standard greenish Bordeau bottles from regional distributors by the pallet. (e.g. Vitroval USA, www.vitrovalusa.com ). In bulk, they cost around $0.50 per bottle.

The wine flows from the elevated mixing tank by gravity to the bottling machine. We sparge the bottles (i.e., filled halfway with Argon) before filling them with wine. Sparging has two purposes: first, it reduces the wine's contact with oxygen as it pours into the bottle. Second, it fills the headspace; the airspace is left to make room for the cork, with the inert gas, to reduce oxygen contact while the wine matures in the bottle.

The bottles are placed by hand under one of two spouts, and the filling machine (Zambelli Tivoli2, http://www.zambellienotech.it/index.php/en/products/enologia/item/filling-machine-tivoli, purchased from Napa Fermentations) automatically fills each bottle to a predefined level. Each bottle is handed to the person operating the corker and the foiler when full.

Corking

As we plan for extended bottle ageing, we buy high-end corks. Our supplier is Portocork in Napa, http://www.portocork.com and we end up paying around $0.75/piece for natural corks.

Our corking machine (Zambelli Bacco Vacuum Corker, http://www.zambellienotech.it/index.php/it/zambelli-prodotti-enologia/enologia/item/linee-di-imbottigliamento, purchased from Napa Fermentations) is fully pneumatic. A vacuum is created before the cork is pushed in and the pushing action is created by pressurised air. So we need both a compressor and a vacuum pump to operate the corker.

Capping with a Foiler

Foils are put over the top of the bottle to protect the cork from mould formation. While mould is no longer a significant threat, foil tops survived mostly for aesthetics. Foils are today made from thin heat-shrinking plastic or metal slightly larger than the bottle top. They shrink and form a tight seal when the Foil Spinner is lowered over the bottle top.

Our Foil Spinner is Italian made (Binello - Alba); we purchased it from Napa Fermentation. We buy our foils in boxes of a thousand from Ramodin USA in Napa (www.ramondin.es/en/ ).

Labelling

We decided to design and print the labels in-house and affix them to the bottles ourselves, as with all other steps. This requires equipment choices (label printer, software, and labeler). Because we do not sell our bottles, we have the freedom to design labels without artistic or content restrictions – for commercially distributed wines, the government specifies what can and must be on each bottle label.

Equipment Choices: We purchased a special-purpose label printer in 2012 (Zeo! from QuickLabel Systems, www.quicklabel.com) with an associated spooler, label design & printing software, plus rolls of label stock. This was a poor choice because the software and the printer are poorly designed, and the company refuses to upgrade the software to work on Windows operating system beyond XP – thus, we need to maintain an old PC running Windows XP dedicated to the printer! The company introduced a new printer at twice the price - lousy customer service. In recent years we have thus switched to an external label-printing service Fernqvist Labelling Solutions in Mountain View, CA (www.fernqvist.com/); the material and printing costs for a simple design are around 50 cents per label.

We bought a basic electric labeler (Bottle-Matic II, from Dispensa-Matic, www.dispensamatic.com/bottle-matic/ ) which works very well, is ideal for our requirements, is reliable, and is easy to operate. With it, we can easily label around 150 bottles per hour

Labels Produced

We decided to produce very classic labels with a fair amount of information about how the wine was made on the back label. We also manually number each bottle.

2009: we produced three very similar labels: one for each type of cellaring we tried out. "2009 oaked" for the 450 bottles we got out of mixing the contents of the new French oak barrel with half the contents of the neutral American barrel. "2009 unoaked A" for the 150 bottles we got out of the neutral American half-barrel, and "2009 unoaked B" for 150 bottles we got out of the remaining half of the neutral American oak barrel.

The back label texts were similar; for the "2009 oaked," it read: This wine is made entirely from Cabernet Sauvignon grapes grown, vinified, and bottled at 21891 Via Regina, Saratoga, California. We harvested 1.3 tons of grapes at 23.6 Brix on October 10, fermented without the addition of yeasts over 2 weeks, and pressed into 2 ½ barrels plus top-up carboys. The wine was aged for 27 months in a new French oak barrel and 1 ½ neutral American barrels. The goal was to produce a benchmark wine. In March 2012, we blended the entire French oak barrel with half of the neutral American barrel and filled 450 bottles labeled "oaked." The remaining neutral wine filled 150 bottles, labeled "neutral A" from the half barrel and "neutral B" from the full barrel. Chief winemaker Aran Healy, assistant Till Guldimann. / This is bottle # of 450. / Government Warning: (1) According to the Surgeon General, women should not drink alcoholic beverages during pregnancy because of the risks of birth defects. (2) Consumption of alcoholic beverages impairs your ability to drive a car or operate machinery and may cause health problems. Contains sulfites. Alcohol 13.5%. General Warning: Consumption of this wine may also make you feel smarter and funnier than your mother ever thought possible."

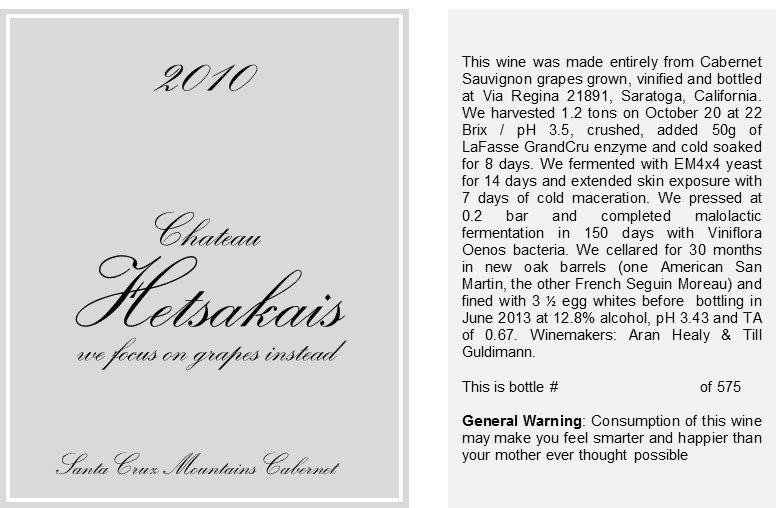

We kept the same front label for 2010 through 2014 vintages but adjusted the back label to reflect the different harvests, fermentation, and elevage strategies. The following pictures show the labels for 2010 and 2011

Starting in 2012, we changed the design of the front label slightly and started using an external printing service (www.fernqvist.com/contact-us )

In 2022 we redesigned the front labels for the vintages of 2015 and beyond. The central idea was to add more information about the weather patterns influencing each. We boiled the weather data down to three critical parameters:

Relative Rainfall: how much rain fell during the vintage year (for the 2015 vintage, this would be from November 2014 through October 2015) and relative to the average for all years on record (2013 through 2021)? This measure summarizes the availability of water.

Relative Sunshine/Temperature: what was the Cumulative Growing Degree Days (CGDD) for the vintage year, and how did it accumulate relative to the average for all the years on record? This measure summarizes the presence of sunshine.

Distribution of Heatspikes: When did the average hourly maximum temperature during the day exceed 95 degrees F. Heat spikes show when excessive temperatures force the plant to shut down.

Note, what matters most for characterizing how the weather influenced each vintage is the deviation from the “average weather.” The absolute weather is a characteristic of the location and part of the “terroir.” The deviation from average is a characteristic of the vintage in that “terroir.” All the data was collected from Davis weather stations located in the vineyard (for more details on our collection of weather data, see the page on Weather Monitoring in the Vineyard Section)

With the help of Gregory Niemeyer, Professor of Media Innovation at UC Berkely (https://www.gregniemeyer.com ), we developed a circular graphic to represent a visual thumbprint of the relative weather conditions for each vintage. The following pictures show the new labels incorporating this graphic for the 2013 – 2021 vintages. The 2013 and 2014 labels are shown for comparison only. Note the wide range of weather patterns across the vintages.

Previous page: Racking & Blending

Top of page: Go

Next page: Bottle Storage

Last updated: July 16, 2018